The African American Experience of Northeast North Carolina (AAENENC) encourages a deeper understanding and recognition for the contributions of the Black community in one of America’s most history-rich corridors. The new self-guided discovery starts online at NCBlackHeritageTour.com and connects dozens of visitable points of interest and African American influence across a six-county region that includes the islands of The Outer Banks, legendary Dismal Swamp and some of the state’s earliest riverfront communities of Elizabeth City, Hertford and Edenton. Discover the African American touchstones the OBX has to share.

The Outer Banks that many visitors celebrate today as America’s best family beach vacation has an incredible backstory that’s ripe for discovery. Buried between the headlines of the first English colony in America at Roanoke Island and the Wright Brothers’ first flight at Kitty Hawk, you’ll find the heroic saga of strong men and women who pioneered some of the first tastes of freedom and equality for African Americans in the country on these very shores in the days leading up to and following the nation’s greatest divide.

To get a quick contextual overview, the Outer Banks were once a mainly sandy barren chain of islands with few trees and mostly a frontier existence for the few thousand people who scratched out a life far from the city. From the first English European onset in America that began with the Lost Colony of Roanoke circa 1587, through the days of piracy in the early 1700’s with Blackbeard’s haunts of the coast, to small family centric communities that still exist today who began and survived as fishing villages and ports of call for mariners in the sea trade leading up to the Civil War in 1861.

There was a little more in the way of agriculture near Manteo, but no big plantations there or in the beach communities of Kitty Hawk, Nags Head or Hatteras that might define most people’s classic view of the South during this time and therefore not much economic need that would substantiate a large slave population. In fact, most of the locals’ political sentiments were aligned with the North, but the South needed to strategically hold the North Carolina barrier islands in the interest of keeping the seaborn supply chain open to feed the war effort. This is where we pick up our tour.

Roanoke Island

Etheridge Homestead | Island Farm

Explore Island Farm, a living history site interpreting daily life on Roanoke Island in the mid-1800s. Living on the bounty of the surrounding waters while working the land to feed their families, islanders were independent and enterprising. The Etheridge family of today’s Island Farm goes back all the way to 1757, working the land and water for crops and fish to trade with communities farther north.

The Etheridge’s were a slave owning family, and one former resident who would make his mark in history was Richard Etheridge. He was born a slave, the illegitimate son of John B. Etheridge, a white man of influence and father of the Adam Dough Etheridge who built the Island Farm mansion house. Richard was favored and well-treated by his father/owner. Unlike most African-Americans in the 1850s, Richard was literate as a young man when even large numbers of whites could not read and write. He also became an expert waterman familiar with the shoal waters around Roanoke Island, skills which would serve him well later in life as America’s first Captain of an all-African American US Lifesaving Station at Pea Island, a precursor to today’s US Coast Guard.

Another compelling story told at Island Farm is that of Crissy Bowser, or “Aunt Crissy”. The census is unclear if she was born a slave or free in 1820, but she served the Etheridge family for most of her life, even building her own home under a 200-year-old oak tree near Island Farm where she lived alone and independent, keeping animals and cooking for the family into the 20th century until her passing in the cabin she’d built with her own hands.

The Freedman’s Colony 1862-1867 | Fort Raleigh National Historic Site

-National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom-

On the heels of the Union’s first military victory of the Civil War at Fort Hatteras in August 1861, Northern forces took Roanoke Island in 1862 in another of the earliest Union military victories over the Confederates. Escaped slaves seeking the army’s protection began pouring onto the island. In response, the army seized local property to use for the establishment of a Freedmen’s Colony on the north end of the island across the street from where the NC Aquarium is today. Some of the former slaves helped rebuild the forts on Roanoke and Hatteras islands and others found jobs such as cooks, woodworkers and blacksmiths. Still others became army scouts, spies, or enlisted in the Union Army. At its peak population, there were nearly 4,000 former slaves from across the east who had made their way to Freedman’s Colony. When the war ended, the land was returned to the original owners. With no home to call their own, many former slaves left the island. Of the few families who remained, many were able to do so because Richard Etheridge of black lifesaver fame sold them portions of property that he had acquired. Many Freedmen’s Colony descendants still live on the Outer Banks.

While the Freedman’s Colony no longer exists today, you can experience its spirit and learn at Fort Raleigh National Historic Site. There’s a memorial that acknowledges the site as part of the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom and a section of the Lindsay Warren Visitor Center at Fort Raleigh dedicated to the Freedman’s Colony. Join park rangers to explore the history surrounding the Civil War battle of Roanoke Island and the establishment of the Roanoke Island Freedmen's Colony. The park anticipates offering this program at the First Light of Freedom Monument regularly during the summer; check our website at Calendar - Fort Raleigh National Historic Site (U.S. National Park Service) (nps.gov) later this year for details.

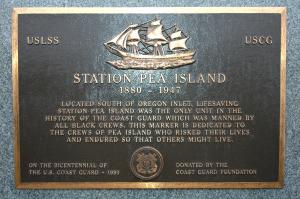

The Freedman’s Colony 1862-1867 | NC Aquarium on Roanoke Island

Richard Etheridge (1842-1900) and his family were buried on property that he purchased in the vicinity of the former Freedman’s Colony, and today you can visit his gravesite and public memorial adjacent to the N.C. Aquarium on Roanoke Island. Inside the Aquarium, you can enjoy a gallery of original portraits painted by local artist James Melvin in tribute to their legacy as part of your experience. Of the 609 documented rescues at sea by the Pea Island Lifesaving Station crew during its operational history from 1880 to decommissioning in 1947, the most famous was the rescue of the crew of the E.S. Newman during an October 1896 hurricane. Richard Etheridge was the first African American to hold the rank of Keeper of a life-saving station. This meant that, under the racial standards of the times, the entire crew under his command would have to be black. Although other black men had served as surfmen at Pea Island and other stations, Pea Island Station came to be manned entirely by a black keeper and crew.

Richard Etheridge (1842-1900) and his family were buried on property that he purchased in the vicinity of the former Freedman’s Colony, and today you can visit his gravesite and public memorial adjacent to the N.C. Aquarium on Roanoke Island. Inside the Aquarium, you can enjoy a gallery of original portraits painted by local artist James Melvin in tribute to their legacy as part of your experience. Of the 609 documented rescues at sea by the Pea Island Lifesaving Station crew during its operational history from 1880 to decommissioning in 1947, the most famous was the rescue of the crew of the E.S. Newman during an October 1896 hurricane. Richard Etheridge was the first African American to hold the rank of Keeper of a life-saving station. This meant that, under the racial standards of the times, the entire crew under his command would have to be black. Although other black men had served as surfmen at Pea Island and other stations, Pea Island Station came to be manned entirely by a black keeper and crew.

Haven Creek Baptist Church | Manteo

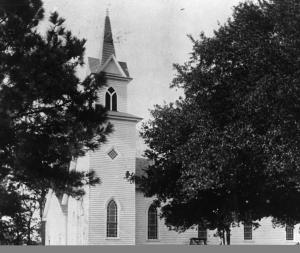

Former slaves brought faith and love of worship services with them to the Freedmen’s Colony. Haven Creek Church in Manteo began during the Civil War when Freedman’s Colonists gathered beneath a tree to worship. During the war, enslaved friends were sent word that if they would come across “the creek,” there was safe haven waiting. Many of the former slaves had escaped from areas where churches had slave galleries with locked doors to keep them from running away during the services. After the war, the formal church was built on property deeded to Richard Etheridge from local white farmer John B. Etheridge, and the congregation chose a name to serve as a reminder of those turbulent years.

Former slaves brought faith and love of worship services with them to the Freedmen’s Colony. Haven Creek Church in Manteo began during the Civil War when Freedman’s Colonists gathered beneath a tree to worship. During the war, enslaved friends were sent word that if they would come across “the creek,” there was safe haven waiting. Many of the former slaves had escaped from areas where churches had slave galleries with locked doors to keep them from running away during the services. After the war, the formal church was built on property deeded to Richard Etheridge from local white farmer John B. Etheridge, and the congregation chose a name to serve as a reminder of those turbulent years.

The Pea Island Cookhouse Museum | Manteo

The Outer Banks has the distinction of being home to one of the most highly-awarded rescue crews in the history of the U.S. Coast Guard, the all-black surfmen of Pea Island Life-Saving Station who earned Gold Lifesaving Medals posthumously for valiance protecting mariners in peril along our coast, and in particular the rescue of all hands of the doomed three masted schooner E.S. Newman.

From 1880 until his death in 1900, former Roanoke Island slave and Civil War veteran Richard Etheridge led a segregated team to guard a several-mile stretch of beach near where the new Captain Richard Etheridge Memorial Bridge is today at Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge. The original main station is long lost, but the detached cookhouse was rescued from the ravages of time and rehabilitated into a museum in the heart of Manteo on Roanoke Island where most of the Pea Island lifesavers were from. Having been a Sergeant in the Colored Troops of the Union Army during the Civil War, Keeper Etheridge ran the station with military precision, characterizing his career as one of distinction. One of the most successful missions included the chilling rescue of the E.S. Newman in October 1896 when two of his crew moved through hurricane-force seas to save lives. The cookhouse is where the men would have broken bread, taken their meals and recounted actions of the day. Remember, if you wanted to travel or trade goods back then, you traveled by ship and often passed offshore of the Outer Banks. Wrecks occurred just like they would along an interstate today, usually in foul weather with the high chance of drowning or worse. The men of the U.S. Lifesaving Service, as the U.S. Coast Guard was known prior to 1915, were among the most heroic first responders of their time.

The buildings are surrounded by the Dellerva Collins Memorial Gardens. Mrs. Collins served on the Town of Manteo Board of Commissioners for more than 26 years, including several years as Mayor Pro-Tem, and was one of the founding members of the Freedman’s Colony Coalition. She married Frank Collins, who served in the US Coast Guard until his death while serving on active duty. Her ancestors played an important role in the Pea Island legacy. The Pea Island Cookhouse Museum is located at 622 Sir Walter Raleigh Street adjacent to the Collins Park and Collis’ Playground, a few blocks opposite downtown Manteo.

Herbert Collins Boathouse | Downtown Manteo

In honor of former Lieutenant Herbert Collins, the boathouse was opened and dedicated in his name in October 2010. Born in 1921 on Roanoke Island, Lieutenant Collins is often referred to as the last Keeper of the Pea Island Lifesaving Station. His career at the station spanned from 1940 - 1947 but he remained in the U.S. Coast Guard for 34 years serving at numerous sea and shore assignments after leaving that station. The boathouse contains a Monomoy type Surfboat on loan to the Pea Island Cookhouse Museum by the National Park Service. It is a representation of the same type of Surfboat that would have been used by Lieutenant Collins and the many other African American men who bravely and honorably served at the Pea Island Lifesaving Station for over sixty years.

In honor of former Lieutenant Herbert Collins, the boathouse was opened and dedicated in his name in October 2010. Born in 1921 on Roanoke Island, Lieutenant Collins is often referred to as the last Keeper of the Pea Island Lifesaving Station. His career at the station spanned from 1940 - 1947 but he remained in the U.S. Coast Guard for 34 years serving at numerous sea and shore assignments after leaving that station. The boathouse contains a Monomoy type Surfboat on loan to the Pea Island Cookhouse Museum by the National Park Service. It is a representation of the same type of Surfboat that would have been used by Lieutenant Collins and the many other African American men who bravely and honorably served at the Pea Island Lifesaving Station for over sixty years.

Lieutenant Collins is a member of a local Roanoke Island African American family that has over 400 years of continuous service in the U.S. Life-Saving Service /U.S. Coast Guard, one of the longest records in Coast Guard history. A family tradition with a long-lasting contribution to local history and the history of the United States. The Herbert M. Collins Boathouse is a part of the Collins Park project, joining the Pea Island Cookhouse Museum and the Richard Etheridge statue. Enjoy a first-hand experience with history at the Herbert M. Collins Boathouse, located adjacent to the Pea Island Cookhouse at 622 Sir Walter Raleigh Street, a few blocks opposite downtown Manteo.

Hatteras Island

Hotel De Afrique | Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum

-National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom-

The first Union military victory of the Civil War concluded August 29, 1861 with a naval bombardment and amphibious assault of Confederate forces at Fort Hatteras and Fort Clark, the former being near the location of the Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum today. Prized for their strategic military value overlooking Hatteras Inlet, the ensuing capture of the Confederate forts had a dramatic consequence. Fugitive slaves began arriving daily in the new Union foothold, hoping for a taste of freedom. Union soldiers had to quickly assemble a shelter to accommodate the influx of refugees forever known to the public as the Hotel De Afrique following a New York Times article on January 29, 1862.

What began as a simple shanty structure quickly grew to about a dozen barracks where African Americans would exchange their skills as watermen, horsemen, laborers in exchange for food and shelter. It was the first such haven for fugitive slaves in North Carolina. Visitors to the Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum will notice a large black memorial near the main parking area describing the Civil War epic battle and ensuing freedom camp. The Hotel d’ Afrique operated from 1861-1865 and is part of the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom.

People in Spotlight

Remembering Mrs. Virginia Tillett | Manteo

Many descendants of slaves who escaped bondage in the Freedmen’s Colony have made immeasurable contributions to today’s Outer Banks community. The late Virginia Tillett was a Manteo native and colony descendant who became the first African-American elected to the Dare County School Board and to the Dare County Board of Commissioners. A recipient of the Citizen of the Year Award from the Outer Banks Chamber of Commerce, she also was presented with the Order of the Long Leaf Pine, the North Carolina’s highest honor.

Many descendants of slaves who escaped bondage in the Freedmen’s Colony have made immeasurable contributions to today’s Outer Banks community. The late Virginia Tillett was a Manteo native and colony descendant who became the first African-American elected to the Dare County School Board and to the Dare County Board of Commissioners. A recipient of the Citizen of the Year Award from the Outer Banks Chamber of Commerce, she also was presented with the Order of the Long Leaf Pine, the North Carolina’s highest honor.

Download a printable version of this article by clicking below.